Mike Kelley

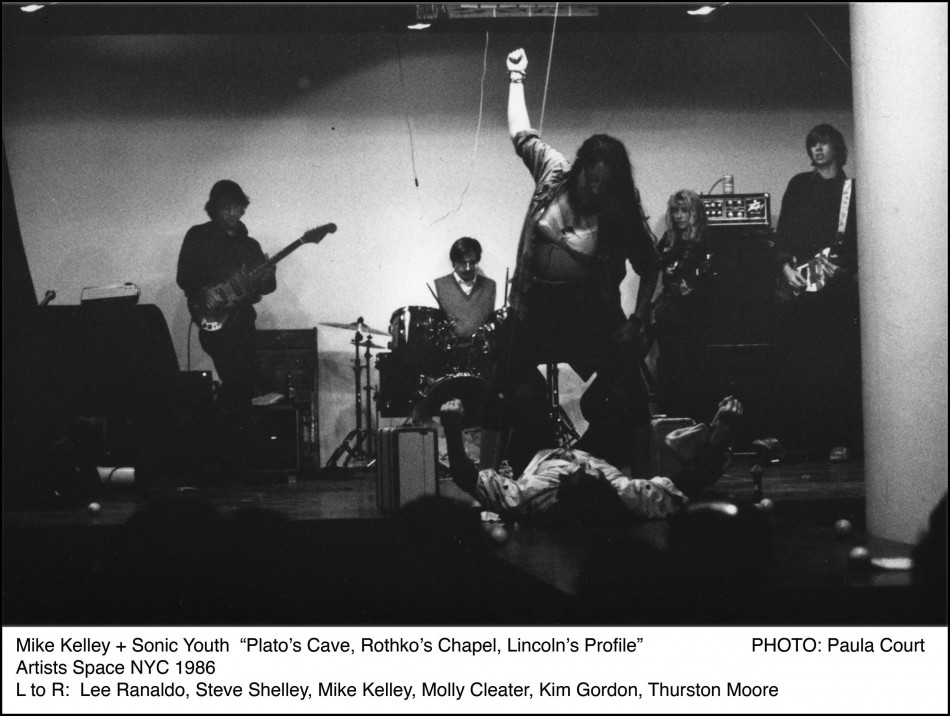

I was very saddened to hear about the passing of our long-time friend, occasional collaborator and continued source of inspiration, Mike Kelley. Kim knew Mike from their days in art school in L.A., and I first met him on one of our early trips to the west coast in ’84 or ’85. In 1986 he asked SY to collaborate with him, writing music and performing live for his performance piece “Plato”s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile” at Artist’s Space downtown. It was quite a trip, and we remained in touch ever since. A photo of one of the performances, by NYC photog Paula Court, is below, as well as a vintage audio recording of the piece. In addition to his art practice, his band Destroy All Monsters also amazed and inspired us, and we were ecstatic to host Mike and longtime collaborators Cary Loren and Jim Shaw for an amazing performance in L.A. in 2002 when we hosted the All Tomorrow’s Parties music festival there. A clip from that show, shot by Chris Habib, is below as well. In 2009, as part of Performa ’09 in New York, Mike presented “A Fantastic World Superimposed on Reality: A Select History of Experimental Music” over two nights at the Gramercy Theater. Both Thurston and I participated, and both nights provided an incredible look at the history of experimental music, thru Mike’s eyes, of course. In the wake of Performa ’09, Mike and I had a recorded conversation about “noise” and “music” which was published last year in the book “Performa ’09: Back To Futurism”. You can read it below.

NY Times Obituary HERE

AUDIO of this performance of Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile (38 min) HERE.

THE ART OF NOISES: MUSIC/RADIO/SOUND

In Conversation: Mike Kelley and Lee Ranaldo

Moderated by Mark Beasley

Mark Beasley (MB): In 1977 the composer and writer R. Murray Schafer described “noise” as any unwanted sound that is out of place. What do the terms “noise” and “experimental music” mean to both of you?

Mike Kelley (MK): I’ve always thought of experimental music as music where the outcome isn’t predetermined. Like in a scientific experiment when you have an idea about something and then you see if that idea plays out in practice, but you don’t really know what’s going to happen. Whereas noise, traditionally, would be something outside of music, or an unwanted sound. I think in more generic usage, it’s just a sound that’s considered unpleasant. And it’s also generally considered transgressive.

Lee Ranaldo (LR): The term “noise” is a funny one, because when Sonic Youth was first getting started in 1980 and ’81, club owners were using the term in a derogatory sense to describe the downtown scene. One club owner was even quoted in the SoHo Weekly News as complaining, “You know, that downtown scene is all just noise.” Shortly thereafter, Thurston [Moore] copped the term and turned it into a cause celebre, staging the “NoiseFest” for 9 nights at White Columns Art Gallery in Soho, in August of 1981. If you ask me what the term itself means, I would say that it’s not really a very effective descriptive term, when applied to music. Maybe it means something more dissonant, or unpleasant, or un-harmonic…but if you take as your basis that music is all about various textures and how they’re structurally arranged, noise is just another element that one can use.

MB: So Mike, how did you first become interested in this kind of music? On the Noise Panel we had, didn’t you say that you weren’t allowed to take vocal classes in Catholic school because they thought you had a bad voice?

MK: Yes—they wouldn’t let me sing – even in the classroom. There were no music classes, so occasionally students would sing religious or folk songs in a regular class, but I wasn’t allowed to sing because I did not have a “harmonious voice.” And then later, when I switched to public school in ninth grade, I wanted to take music but wasn’t allowed to because I didn’t have any background in it. And it was the same when I went to CalArts to attend Graduate School. I wanted to study with Morton Subotnick, but because I had no music training, I wasn’t allowed to take music theory courses. So basically, my whole life, whenever I’ve tried to get involved in music, I’ve been institutionally denied.

LR: It’s funny what you say about being rejected from the various academic possibilities of learning about music because you weren’t already trained. It’s a catch-22: you have to be trained in order to get in, and you can’t get in until you’re trained! That’s why one might turn to experimental music—because you don’t need any qualifications, really. It’s a very leveling field. Anyone with an idea is in. It’s the ideas that are most important, rather than any sort of technical skill.

MB: So how did you first become interested in these kinds of music?

LR: I was exposed to a lot of music at home. My mother was a pianist, and I sang in choruses all through grade school and high school and played guitar and piano. But when I started to get serious about the idea of making music myself, it was separate from the moorings of my training. I was more inspired by what was coming out of the radio: first AM radio pop music, and later, rock’n’roll music. Yet even at that time there were certain formal codes and structures to making rock music, which—in my limited capacity as a player—I was unable to hit. So I was forced to branch out to try to create my own language.

MB: Do you think there was a generational discord, or moment, when the meaning of “noise” changed?

MK: Well, I think that in the beginning, electric rock music was considered noise music because of the volume and the distortion; at first, the whole point of electric rock was to be noisy, so there was a generational split right there.

LR: That’s true. All amplified music was once seen as transgressive by a large section of society, especially as it got louder and weirder. “If it’s too loud, you’re too old!”

MK: Exactly. Then things started to go in a more psychedelic direction. And once you hear someone like Jimi Hendrix, with all of the feedback and distortion, it’s not a big leap to start playing the electronics themselves. For anyone who grew up in an industrial area, these sounds were already very common; for me, coming out of Detroit, it was natural to go in that direction.

LR: A lot of people have talked about noise music being heavily influenced by environment, saying that of course noise came up in New York and Tokyo, because those are big loud cities with lots of noise everywhere. It seems obvious, but it’s also fairly true. There are times where I walk around New York, and if there’s a lot of construction going on—with the sounds of pile drivers and whatnot echoing off of the buildings—you start to hear these amazing rhythm tracks. I’ve got tons of recordings of stuff like that—“noise music” came about as a reflection of the city around us, and social situations.

MK: Definitely. William Burroughs’s tape experiments were very influential on me because they started with recordings of environments. To him, sound was a kind of weapon. He took ambient recordings, cut them apart, and re-pasted them together to reveal the world by shifting its syntax, and bringing all of the background noise that we (normally filter out) to the foreground—a very radical idea that John Cage had already been doing.

MB: The art historian Brandon Joseph has talked about the political dimensions of noise before—for example, New York City’s EPA department once published a pamphlet called “Noise Makes You Sick,” and some have argued that noise control guidelines have been misused to control African American neighborhoods like Harlem and Brownsville, to prevent more housing developments from being built—the idea being that noise is this scary force to white middle-class people living in cities. Living in Detroit, Mike, did you feel that noise was used politically in any way?

MK: Not political in a conscious way. In poor areas, loud motorcycles, cars, and boom boxes are statements of identity – they function as a kind of audio graffiti. Similarly, raucous popular music generally functions as the voice of disfranchised people – including youth.

MB: What were the politics of Destroy All Monsters?

MK: We developed out a specific late Sixties Detroit music scene where noise – loud rock music – was used in a confrontational manner and linked to the politics of the new left. Concerts organized by the anarchist White Panther Party mixed populist rock and experimental music in an attempt to radicalize local youth. But that scene died at the end of the decade with the collapse of the local economy.

Destroy All Monsters addressed the failure of that utopian dream by doing a more nihilistic version of it. We were very exploratory—we didn’t have “one sound.” I lived in a house with jazz and rock musicians, and often our recordings were jam sessions with very different kinds of players, just exploring sounds without any particular focus. Though I was particularly interested in avant garde music, psychedelia, and free jazz.

MB: And Lee, what politics do you think were informing Sonic Youth?

LR: Well, I’m actually thinking pre-Sonic Youth, when I was a teenager starting to play rock music. At that time the socio-political element was basically that you didn’t like your parents’ music. Young people were looking for more challenging stuff to listen to. By the time I left high school, my interest in rock had changed into an interest in twentieth-century music of all sorts, from the Futurists through John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Henry Cowell. And lots of those directions came about as a result of things like the Beatles more experimental later tracks—their influence , and, for example, San Fransisco psychedelic music pushing the boundaries of what the listening experience could be. I think young people wanted to feel like the field was wide open, so that you could do whatever you wanted.

MB: Then, to connect your and Mike’s practices—I understand that Sonic Youth provided the soundtrack for Mike’s piece Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile at Artists Space in 1986. How did that collaboration come about?

LR: I think Mike and Kim [Gordon] had been friends in LA. Mike was coming to New York to do this piece at Artist Space and asked us if we would work with him. Steve [Shelley] had just come aboard as our permanent drummer, and we were at the point where we were past just trying things, and had really formed a language that we were all comfortable working with.

MK: That’s right—I knew Kim in LA before she moved to New York. At that time she was not yet a musician; she was a visual artist. I watched the development of Sonic Youth, and I liked the music and I liked them as people. In that particular performance I wanted to have a live sound element modeled after kabuki theater, where there are musical sections that play off the language in a quite disjointed way. I also wanted to play with the idea of rock staging. A lot of the audience was there to see Sonic Youth specifically, because at that point they were a known band, so I had some parts where the band was really foregrounded and others where they were completely hidden—behind a curtain, for instance—so you couldn’t see them. And it was great, because they sometimes were doing music not at all typical for Sonic Youth—at one point, for example, I asked them to repeat a riff from “Train Kept A-Rollin’” over and over.

MB: Moving forward in time, would you say that noise could be described as a transgression that changes with each generation?

MK: Definitely. I’m hearing a lot of music now that’s obviously a reaction against the noisiness of punk and post-punk—like psychfolk. That’s a generational transgression.

LR: There’s a whole category of what I call “noise-icians”—people who are dedicated to playing pure noise music—that came to people’s attention in the nineties with Japanese bands like Violent Onsen Geisha and Boredoms. So today there’s a whole group of younger people for whom this is their background—it’s like their Beatles. When Sonic Youth was developing, we were integrating pop structures with very abstract, or noisy, sounds, trying to figure out ways to meld them both. We were children of AM radio, and grew up listening to pop music, but also being exposed to all sorts of avant-garde movements like I was talking about earlier, so we didn’t want to abandon one for the other.

These days there are so many young people who are specifically noise musicians that it almost puts them into a ghetto. It’s become a genre, so for young people it’s not transgressive anymore: you’re either into it or you’re not.

MK: Exactly. I was really surprised when I first went to Japan with Destroy All Monsters—we played in front of an auditorium packed with teenagers. They’re so fascinated with obscurities there. To them “noise” music was like punk was for American kids—but, they were mixing, like John Cage with hardcore. It was all exotic music to them, outside of their culture, so they didn’t have the same inherited inhibitions about crossing these musical borders. I was so shocked by this, I found it hard to believe that noise music could be popular teen music.

LR: When Destroy All Monsters was around, did you feel like you guys existed in a kind of void? Now noise bands can go out and get tours all over, but then, it was either being part of the established music scene or nothing.

MK: Yeah, we couldn’t even play in a club. They’d kick us out.

LR: Sure. It was the same thing when Sonic Youth was starting out—we had a hard time getting gigs because people didn’t understand the music.

MB: Were you accepted by the art world? Could you play in galleries?

MK: No—we weren’t accepted by the art world or the music world, so we operated in a kind of guerilla way. We would crash house parties and play there; or we’d play at loft parties for three or four people, after the rest had fled. We existed in more of a conceptual way, rather than as part of a scene. But that really changed with the rise of punk. When I moved to California, I tried to move into the punk scene with my band the Poetics, which included Tony Oursler and John Miller. Some of the musicians associated with the Los Angeles Free Music Society (LAFMS) were attempting to do the same thing, but that was a very odd marriage. All of my attempts to fit into different music scenes didn’t work; at a certain point, I lost interest and decided to do solo work that was specifically geared towards the performance art audience, keeping out of the music world entirely.

LR: I had a band in college called Black Lung Disease, a kind of psychedelic abstract music combo, that reminds me of what you’re saying about Destroy All Monsters. You guys only played a few gigs the whole time you were around. I remember that we played a lot—but we didn’t play for a lot of people. It was almost like we were alone in a laboratory experimenting, and the laboratory happened to be someone’s living room, or wherever you could set up a drum kit. Only an incredibly tiny group of people—the players and a few friends—ever heard us. It wasn’t a scene; it certainly wasn’t a profession or a career.

Once it gets to the level of these noise bands today, touring all over and playing in clubs, it’s hardly even ‘experimental’ anymore. There’s something very codified about it at that point; audiences coming to see it know exactly what it is. Maybe experimental music is something you’re only afforded the opportunity to create when you’re young and unknown—when you’re trying stuff purely for your own edification, to see where it goes…

MB: Mike, it was an honor and an education to work with you on the noise music festival. Could you tell us about creating A Fantastic World Superimposed on Reality, or the two-day noise festival that we had as part of Performa 09?

MK: Sure. The noise festival was a dream come true. I had the opportunity to put together ,on one bill, a selection of performers that I really admire. I kept it to a particular generation to provide focus, but I also wanted to include the kind of classical avant-garde pieces that influenced these people. So, it was a mix of musicians and artists primarily associated with the downtown New York scene of the late sixties and seventies along with improvisational and experimental musicians of the same generation from other locales – especially Los Angeles.

MB: And what about your take on the West Coast scene that you came out of?

MK: A good history of American improvisational music of Lee’s and my generation has yet to be written. The West Coast scene, in particular, is poorly documented. There are many written histories of punk, but no one has written about the art band phenomenon. When I moved to Los Angeles in 1976 I became acquainted with the LAFMS – improvisational artist/musicians of my age who were producing their own records. The West Coast was one of the most important centers for has come to be known as “industrial” music, with artists like Boyd Rice, John Duncan, and “synthpunk” groups like The Screamers. The Screamers were very popular in Los Angeles but they refused to release studio recordings of their music. Few recordings exist of many of these groups. That’s why I felt it was important to include groups like Airway in the festival. It was the first time, to my knowledge, that any LAFMS-related band had played in New York, and the first time that Destroy All Monsters played in New York.

MB: Which is incredible. Lee, what did you think of the festival?

LR: I performed in the recreation of Steve Reich’s Pendulum Music and watched everything on the first night. I loved the fact that it was drawing from a very specific time period because I think that if it had extended further, it would have moved into a place that was much better-known to the crowd that was there. I liked that it presented stuff as varied as throwing potatoes at a gong and the Steve Reich piece…in a way, it was like Mike’s diary of musical pieces from that period that had an influence on him, which I thought gave it this really nice sense of focus.

MB: Yes, it was woven together by Mike’s personal narrative. And it was also provacative in suggesting that at a certain point, true “noise” ceased to be-it’s become something that future generations will have to define anew. It was quite a provocation to subsequent generations in relation to those histories…

I found this transcribed conversation very interesting, especially for Lee Ranaldo’s comments about his early musical formation and that of Sonic Youth.Thank you for making this available. Mike Kelley, RIP.

Pingback: Lee Ronaldo on Experimental Music | BE_NG IS N_T DOI_G

Pingback: artist mike kelley dead at age 57 | tomorrow started

Pingback: Le blog de multimedialab.be » Archive du blog » Mike Kelley (1954-2012)