LR Interview – Magenta Magazine Oct 2011

Here’s a recent conversation between Toronto artist/curator Dave Dyment and myself while Leah and I were up in Toronto presenting Contre Jour.

http://www.magentamagazine.com/8/features/lee-ranaldo

New York Noise: Sonic Youth’s Lee Ranaldo creates art that strikes a chord

10/27/2011

Fans of alternative rock and experimental music probably need no introduction to Lee Ranaldo, who, as co-founder of the influential Sonic Youth, has been acknowledged as one of the greatest guitarists of all time. Ranaldo studied art at Binghamton University and has frequently produced sound, performance and visual art independently of the band…

Lee Ranaldo: Contre Jour, performance with Leah Singer at SPK in Toronto, October 21, 2011. Above photos: Tara Fillion (top), Leah Singer (below); all images courtesy the artist.

By Dave Dyment

Fans of alternative rock and experimental music probably need no introduction to Lee Ranaldo, who, as a co-founder of the groundbreaking New York-based band Sonic Youth, has been acknowledged as one of the most influential guitarists of the last 30 years. Formed in 1981, Sonic Youth, whose members include Ranaldo, Thurston Moore, Kim Gordon and Steve Shelley, would go on to redefine rock music with albums such as Sister (1987), the epic Daydream Nation (1988), Goo (1990) and Dirty (1992). The band also has close ties to the art world, with several notable visual artists, including Gerhardt Richter, Raymond Pettibon and Mike Kelley, providing the artwork for the band’s albums.

Ranaldo studied art at Binghamton University and has frequently produced sound, performance and visual art independently of the band. He has released over fifty solo, band and collaborative recordings, and a dozen books, including travel journals, poetry and artists’ books. His work has been exhibited at numerous galleries and museums, including the Hayward Gallery (London), the Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art, NSCAD (Halifax), the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, Mercer Union (Toronto), and Printed Matter, Artspace and White Columns (all NYC).

On October 21, 2011, the Music Gallery, InterAccess and the Images Festival presented the North American premiere of Ranaldo’s Contre Jour, a performance piece for swinging guitar, with visuals by longtime partner and collaborator Leah Singer. The next day, Toronto-based artist and writer Dave Dyment and Ranaldo found a quiet corner at the Art Gallery of Ontario, where they discussed Ranaldo’s recent projects, the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York and, with the recent announcement of Gordon and Moore’s separation, Sonic Youth’s future.

Dave Dyment (DD): The addition of the drummers in the performance last night felt like a bit of solidarity with the Occupy Wall Street movement, which essentially began a few blocks from your home. Can you talk about your relationship with the protestors at Zuccotti Park?

Lee Ranaldo: Black Noise (2008): Drypoint on vinyl record, edition of 8, 15 x 14.5 inches.

Lee Ranaldo (LR): I’m very supportive of it. They march past our door practically every day. It’s a pretty lively, joyous movement and there’s a parade of people walking up the street daily, with banners and chants and noisemakers and drums. So, just on a level of public street theatre, it’s very good, and I’m finding it to be very effective in the neighbourhood. They’ve been camped out in the park for more than a month now and they’re making their presence known every day, parading around the city and making it clear that they’re not going away and that they’re serious. It’s been interesting. I’ve been down there a lot, at different times of day or night, documenting it.

DD: You’ve been putting photographs on your blog…

LR: Yeah, exactly. It was interesting to walk through Occupy Toronto last night, getting some snapshots that I can also put up on the site. It’s good to see the sympathetic movements that are springing up here, there and everywhere. I’ve been recording their chants, and really loving the way they sound. A week ago I was down at Zucotti Park and there’s a big circle of drummers and a couple other guys – there’s one sax player who’s pretty good – he’s there a lot and he’s kind of like the MC. He stops playing and the band goes on, and he starts telling the crowd why they’re there, what they want and so on. Another guy set up a really rhythmic chant: “Occ-u-py. Wall Street / All day / All week.” With the drum circle behind him, it was kind of like a band with a toastmaster and a vocalist. I thought, ‘these guys have the makings of a good band!’ The chants and the drumming have been of particular interest to me, I’m going to use them in a few things I’m working on. Do you know the festival Performa?

DD: Roselee Goldberg’s [Performance Art] festival?

LR: Yeah. I was involved in ’09 and for that year they were really focused on Futurism and they had rebuilt Luigi Russolo’s noise instruments from around the turn of the century.

DD: Those are some pretty important pieces. A lot of historians credit that as the beginning of sound art.

Lee Ranaldo: Untitled (End) from the Fire Island series (2009): Watercolour on paper. 12 x 9 inches.

LR: Absolutely. But, there’s only a couple of minutes of actual recordings from his original instruments from back in the day, so this Italian composer and conductor named Luciano Chessa reconstructed them for Performa two years ago. They had a big concert at Town Hall and had a variety of people write pieces for them. Text of Light got hold of four of them the following week and did a performance with them and they were really cool to work with. I think we were the first to amplify them.

For Performa 11, in a month or so, they invited me to compose a piece with these instruments for Art Basel Miami. It’s going to be in the new Frank Gehry concert hall there, in conjunction with the New World Symphony. At this point, I’m not sure if I’m writing something just for the noise instruments, or if it will include members of the symphony. I’m thinking of using the Wall Street chanting and maybe even the drumming as elements of the piece.

In many ways, I’ve been less interested of late in presenting the kind of work we did last night, here in Toronto, as a purely solo performance. In some situations, it works really well, but these days I’m finding that it’s better if there are other elements going on. I’ve been doing performances where some of the performers are secreted among the crowd and all of a sudden people start popping up and doing something when you thought they were your fellow audience members a second ago, like the drummers were last night. I did something like that in Paris at the Cartier Foundation two years ago with a spoken word piece. We had all these index cards with the words to some of my cut-up poems on them. All of a sudden, fifteen or twenty people in the audience started spouting these words, and then the cards were handed out to others in the audience and they started speaking them, too. It was kind of like a random poetic event in the middle of the concert.

So, two days ago I wrote to Alex [Snukal] and Jonny [Dovercourt], and asked if it would be possible at the last minute to arrange for some drummers, and somehow they made it happen.

DD: The two most recent times you’ve been to Toronto have been for these collaborative projects with Leah Singer.

LR: Yeah, these ‘suspended guitar phenomena’ projects. The one at Nuit Blanche was… well, it wasn’t the first one we did, but it kind of solidified the form for us and took it to a larger level of spectacle. Over the last year, we’ve done several re-workings of that performance, sometimes with other musicians and a different cut of film for each, and different backing tracks. It’s gone in a few interesting directions.

DD: Am I right in thinking that these collaborations date back to the very beginning of your relationship? Didn’t you meet performing at a film event that she put together?

LR: Yeah, in 1989. We got together the next year and, by 1991, we were doing film and music concerts together, which we called Drift. It’s really evolved from 16mm single projection to double projection and now to digital video with massive screens. Drift – the gallery show (in New York and, later, Europe) – and the box set and all that, was the culmination of the 16mm ‘analog period’, in a way.

DD: Do you find there’s cross-pollination between your practices? I notice, for example, that you both use newspaper imagery in your work.

LR: There’s definitely a sense of giving each other ideas and playing with ideas that each other is working on. There are places where they diverge and certainly a lot of shared interests, especially in terms of photos. Leah was a photo archivist for the Daily News and often used the imagery in her work and at one point I began looking at newspaper photos in a different way myself, and started using them for a series of ink drawings and installations.

It’s funny. I just got a text from a friend of mine a few minutes ago who thought I was in New York and asked if I wanted to see the Bob Dylan painting show at the Gagosian.

DD: At the Gagosian?!

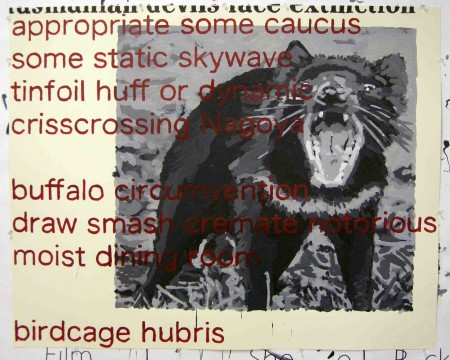

Lee Ranaldo: Tasmanian Devil (appropriate some caucus…), 2008: Ink and oil on paper. 40 x 30 inches.

LR: Yeah, I know. It’s funny. I saw Dylan play about a year ago and I was watching from the VIP area. Larry Gagosian was standing next to me, which I thought was strange, but now I realize that there was maybe some courtship going on. The show, which closes today, is called The Asia Series and it’s paintings of women with baskets on their head leading donkeys, lots of generic Asian imagery. The early reviews were fairly positive, if a bit curious that it was at Gagosian, but then a couple of days later it came out that Dylan was basing a lot of the paintings on photos, including some by Cartier-Bresson and other well-known photographers of that time, reproducing the original compositions exactly! It became a bit of a scandal, but of course that approach is not uncommon in the art world. Most of my own recent drawings are based on found photos, as well. A friend of mine, Clinton Heylin, is a Dylan biographer – well, he writes a lot of rock biographies – and he was scoffing at how cheap it was that Dylan was using these photographic resources, and I told him that perhaps Dylan really was a modernist painter after all!

DD: Well, yours are overt, and you are referencing their origin as newspaper imagery.

LR: Yeah, it’s true. And, it also has to be said that in the catalogue for the Dylan show there’s an interview with John Elderfield, and the quotes from Dylan were all like “I really like to work from life” and “It has to start from real experience”. [Laughs.] It’s all in keeping with Dylan’s myth-making, but it’s also pretty funny.

DD: Do you think that your dual existence with the art world, and your origins, inoculate you a little from the type of criticisms that face Dylan, Paul McCartney, Tony Bennett and other singers who move into painting?

LR: Well, Tony Bennett is a pretty good painter, for what it is. He’s got certain skills.

DD: But he’ll always be thought of as a singer who dabbles.

LR: I think that’ll always be the case for someone who’s known primarily for one discipline. And, probably the more famous you are, the harder it is. I imagine it’s impossible for McCartney to show his paintings without people chuckling, whether they’re good or not. Or,even when he writes music for a ballet, which he’s just done, it’s assumed people are there for other reasons – the cult of personality or something. But, I think I’m lucky enough to have started in a period when it was really seen as artists working in the populist medium of music.

DD: And your beginnings with Glenn Branca, who is as well known in the art world as he is as an experimental composer…

LR: Yes. I came to New York from art school, as a printmaker and painter and guitar player. It’s kind of fascinating with a lot of people, when you know them for one thing and then you discover that they do a lot of things. We were just interviewed yesterday for a Michael Snow documentary and I came to know him as a filmmaker because I was studying with Ken Jacobs and Snow’s work was shown as the epitome of a certain kind of structuralist filmmaking. I didn’t know anything about his visual art practice at that time, and I certainly didn’t know anything about his music practice, which extends back to Dixieland Jazz in the fifties and sixties.

I find that I like artists who are working in a multitude of areas. It’s harder to get a handle on those artists, as opposed to those who are single-mindedly focused and working towards one identifiable thing. But, ultimately, it can be hard for an artist to hold your attention over the years if they only have one thing they do. There are certainly people who do it. James Turrell – we saw his Straight Flush light piece last night on Bay Street – does that. He does one thing but he does it very well.

DD: Can you talk a bit about the bookwork you made with Leah, Water Days?

LR: That book evolved out of two summer residencies at a place called the CNEAI – the Centre National de L’estampe et de L’art Imprimé. It’s a print and book-arts museum that invited us there for summer residencies in 2007 and 2008. We went with our boys and camped there for the month of August in both of those years. It’s right on the edge of Paris; the residence is a modernist house-boat floating on the Seine, right offshore from the museum. It’s really idyllic, in an historic area where Renoir and Monet painted some of their most known works.

We did a lot of printmaking there – that’s where the first Black Noise print originated – I was doing monotypes and etchings, and Leah was doing etchings and some silkscreens. We had a show there in early ’09 and at that time I was invited to make a piece for the radio station Radio France Culture, which invites artists to make sound works with no restrictions – as short or as long as you want. Some of them are three or four hours long. Laurie Anderson did one, Jonas Mekas, Ryuichi Sakamoto, a lot of different people have done them. Dis Voir Editions in Paris publishes the accompanying books, which include a CD of the audio work – mine was an hour long. The book can be whatever you want it to be, a sort of visual accompaniment to the audio track. The CD was all sound recordings made while we were on the boat – local church bells, the sound of the water lapping against the boat, the sounds of the master printer counting down the etching time – un elephant, deux elephant, trois elephant, and so on. Then, I included some voice samples – Smithson talking, Carson McCullers, a bunch of different voices, and created this rather ambient radio piece. Leah and I both wrote texts, which we read and which were also translated into French. So it made sense to have the visuals also be about the residency. It’s kind of a scrapbook of our time there.

The museum also pressed the audio as a vinyl LP, as a kind of catalogue of our show – it had essays by the director and curator on the inner sleeve, and Leah designed a plastic slip-cover for the LP jacket, which was embossed with some of the imagery that she was making into prints at the time (as it happens, abstracted maps of the Canadian provinces).

DD: You mentioned the Smithson quote, and I recall a quote from Brion Gysin in the performance last night. So many of your works reference other artists – titles borrowed from Kerouac, works dedicated to Smithson, Stan Brakhage, Harry Smith…

LR: The piece last night included the Gysin because it was designed specifically for a show in Brussels where Winnipeg curator Anthony Kiendl asked us to do something Gysin-related, based on something he saw us do at the New Museum in New York City about a year ago, when they did the Gysin retrospective. We did a performance with the Dream Machine in the space and Leah created a specific film that was all about light coming from behind, in reference to the way Gysin discovered the Dream Machine. As told in that quote, he was sitting on a bus with his eyes closed and the sun was going through the trees and the flickering light started to create these patterns on his eyelids, leading him to invent the Dream Machines. So, we built that whole piece, especially the filmic stuff, to be about that kind of light and to reference his work.

It’s kind of nice, when you’re thinking about an artist’s work and they’re influencing your thoughts, to make it clear. The Amarillo Ramp (for Robert Smithson) record is just a sound piece but, in a way, tying it to something specific like that piece of his gave it a different kind of focus and also allowed me to acknowledge someone important to me. I wouldn’t want everything I did to require those references, but it’s nice to do every once in a while.

The piece that Leah and I do can be tailored to different situations, so when the New Museum asked us to do the Brion Gysin thing we took a slight tangent from what we normally do and narrowed the focus a bit. Some years before that, the MOCA in L.A. was doing a big Smithson show and they asked us to come and do a performance that was Smithson-related, so I found some texts of his that I read, and some samples of his voice, and Leah tailored the imagery a little. It’s more of an idea of their work, or a feeling you get from it, rather than a literal copying of it.

DD: Your Torn Photograph combines two separate influences, and fairly specifically. Can you recount the story of how that came to be?

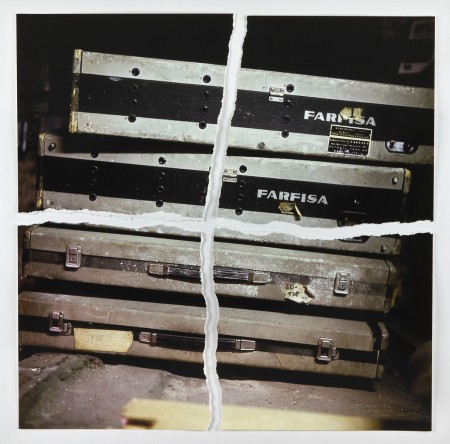

Lee Ranaldo: Torn Photograph: Four Organs for Steve Reich and Robert Smithson (2007): Ink jet print, edition of 10, torn in quarters. 21.5 x 21.5 inches.

LR: [Steve] Reich’s Four Organs piece was very important to me when I first moved to New York. We were listening to his early tape pieces like Come Out and It’s Gonna Rain, but Four Organs just absolutely blew me away. When we moved into our apartment in 1995 I knew that Steve and Beryl lived there and I was in the basement one day – the building has this gigantic, really labyrinthian basement and everyone has a storage locker – and found, literally right outside of our locker, a big pile of musical gear, which I photographed because it looked interesting. Well, it turned out to be all of Steve’s stuff, and the four organs there were the four organs. So I took some more pictures, specifically of the organs and just had them laying around. At some point, I saw the Smithson torn photo and I thought it would be cool to pay homage to both of these people in one work.

The version that Paul + Wendy Projects has available came from a residency we were doing in Sweden in 2000 where they wanted to create a compilation boxed work of multiples called Black Box. I sent them a digital file for the work and the dimensions were wrong and they made a Spinal Tap ‘Stonehenge’ version out of it, considerably smaller than the Smithson piece that it was supposed to mimic! I finally had it printed myself at the correct size, in an edition of ten, a couple years later. Leah, for an anniversary present a few years ago, managed to find and buy one of the original Smithson pieces for me. I have them framed identically and when the Sonic Youth Sensational Fix show happened, we displayed the two works side by side, which was really cool.

DD: A surprisingly large number of the artists whose work you reference are Canadian or have ties to Canada: Brion Gysin, I think, was born in Britain to Canadian parents and then raised in Edmonton, Greg Curnoe, Michael Snow, even the Group of Seven.

LR: I’m not sure how that came about. At some point we were strolling through the Art Gallery of Ontario or the Winnipeg Art Gallery and I stumbled on the Group of Seven. I had an interest in that type of work – the early stirrings of Modernist Painting that was going on in many places around the world – for a long time, and I’m not sure if the Group of Seven just kind of solidified it, or if they sparked it, or what. Others would be people like David Milne here in Canada, Ferdinand Hodler in Switzerland, or Colin Macahon in New Zealand a little bit later, whose work I am really interested in. When I was in Australia some years ago, I discovered a lot of painters from that same period who were doing really interesting work down under – Arthur Streeton, for example. There were so many artists, all over, making interesting paintings in a period that almost got lost between the last throes of Impressionism and the first full-on throes of 20th-Century Modernism. As someone who continues drawing landscapes on occasion that work is still really interesting to me.

I was talking a few months ago with the Director of the Whitney, Adam Weinberg, and mentioned my interest in the Group of Seven and how little known they were in the U.S. and how he should have a Group of Seven show. I was kinda kidding him about it. He, of course, knew and loved the work but, in general, nobody knows that work in America.

Curnoe, too, one of the things that appeals to me about his work is that he was an artist who was really involved in community and locality. Again, the place is important. It’s where the artist lives, what he sees. And, with Curnoe, there are so many interesting parallels for me – artist/musician/cyclist/family man… getting deeper into his visual work over the last few years has been a real revelation.

DD: I’ve been thinking about the fluidity of your practice and wondering, given the variety of media that you work in (sound, drawings, poetry, etc.), if a work ever begins with the germ of an idea that is still unsure whether it wants to be a song or a canvas or a film?

LR: Sometimes an idea sparks fully formed, at least in terms of the media. The newspaper drawings came out of seeing these pictures and wanting to transform them somehow into pictures again, but with a different context. Whereas other times an idea can germinate for quite a while and I’m not sure what manner it should manifest in: poetry, song, visually.

I did an interview about a year ago for a Nihilist Spasm Band documentary, and the crew came and interviewed me in my studio. One of the photographers took some shots of me, in the studio, walking on the street and so on. I really liked the quality of one of the pictures and I thought, ‘this would make a really good album cover.’ And, in a way, that led to the development of the solo record I have coming out in a few months. It was the cover that came first.

DD: Have you ever had your photo on an album cover before?

LR: No, not really. I don’t think so. But this picture really looked like it would work as the cover of a proper album of songs, so I realized I had to make the songs to go with the cover image! Recently, when working on the layout with the record people, I had to explain why the picture was integral to the album, even if that’s not apparent to anybody but me. So, there’s an example of an instance when you just see something and the medium is something you’re certain about, and then you have to set out to actualize it.

DD: This record will be a departure of sorts for you. Am I right in thinking that, apart from the occasional vocal track, the bulk of your solo records have been instrumental?

LR: Yeah, abstract instrumental things for the most part. There’s never been a record of all songs that I’ve written. These are all rock and pop songs, and I’m really, really happy with it. It came out really well, so I’m super-excited about it.

DD: Is it self-produced?

LR: Well…I guess it kind of is. It’s produced by the guy who mixed it, John Agnello, who did the last couple of Sonic Youth records and works with Dinosaur Jr a lot, among others. He mixed it and he’ll get a co-producer credit but, other than that, I guess I produced it myself. It’s coming out in March 2012.

DD: Are you going to tour behind it, with a band?

LR: Yeah, yeah, we just did our first show last week. Steve’s playing drums, Alan Licht is playing guitar – they’re both on the record – and a local bass player named Irwin Menken. John Medeski, from Medeski, Martin and Wood, plays all the keyboards on the record, Nels Cline plays guitar, Jim O’Rourke plays bass on one track, and our old drummer, Bob Bert, plays congas on a couple tracks. It has a bit of a family thing going on, and we’ll go out next year and tour.

We’ve been working on the record for most of the year, finishing it in July, so it’s entirely a coincidence that it’s happening just as Sonic Youth is going on hiatus. I wouldn’t want it to appear that we were rushing it out to fill any kind of perceived void.

DD: Luckily, most people will understand that you couldn’t possibly put together a record in such a short period of time.

LR: Yeah, I hope so. It’s like that authorized biography of Steve Jobs that comes out just three weeks after his death, with the publisher moving the release date up a month to capitalize on the situation. Kind of slightly creepy.

DD: You’ve been friends for over thirty years, and even your non-Sonic Youth projects tend to feature collaborations with each other. Could you ever imagine a time when you didn’t play together?

LR: Well, we’ll have to see what the future holds right now. Steve and I are certainly working together right now on this band project of mine, and I’d be surprised if we all didn’t work on things, whether all together or in smaller groupings, at some point in the future. At this time, the fate of the band is not determined. I expect a prolonged hibernation, at very least, after the upcoming dates we have in South America next month. Plus, we have so much history, so much work together that, no matter what. there will be so many things to tie us together in the future for quite some time…historical, archival releases and other projects of that sort. My motto tends to be “change is good” and I’m hopeful that applies in this case. Anyway, I’m happy to leave it at that for the moment.

To keep up-to-date on tours, exhibitions and other news, visit Lee Ranaldo’s website, www.leeranaldo.com.

Dave Dyment is a Toronto-based artist whose practice includes audio, video, multiples, performance, writing and curating. His work has been exhibited in Calgary, Dublin, Edmonton, Halifax, New York City, Philadelphia, Surrey, Toronto and Varna, Bulgaria. Recent projects include a series of artist’s books, one-hundred year old whiskey and homemade LSD. His most recent book, Pop Quiz, is available from Paul + Wendy Projects. Dyment is represented by MKG127 in Toronto.

Great interview. Lee’s story of finding Steve Reich’s Four Organs in the storage area of his building’s basement is incredible! The photo of them stacked up is perfect. XO

Pingback: en letra minúscula » Goodbye 20th century

good interview. Can’t wait to hear mr. ranaldo and medeski jammin’. Haha and bob bert!