I-View: The Gilt Man Interview 2010

THE GILT MAN Q&A: LEE RANALDO OF SONIC YOUTH

The experimentalist guitar god on the first axe he ever owned, the records that changed his life, and the vintage guitar sale he curated for Gilt MAN.

-By Andy Comer, Friday April 22nd, 2011 at 11:39 am

RANALDO ONSTAGE IN THE LATE-’90S.

For those of us who’ve been even marginally plugged in to independent music at any point over the past 25 years, Lee Ranaldo is a man who requires little introduction. Co-founder in 1981 of the now-legendary guitar band Sonic Youth, Ranaldo—with his radically inventive, aggressively rhythmic playing style (he’s the reason Kurt Cobain would do things like rip the strings off his guitar mid-song, or pound it with a drum stick)—has effectively redefined how the guitar is played as an instrument, and how rock music can and should sound. He’s also a legendary collector of guitars, owning and customizing hundreds over the course of his career. All reasons why we’re thrilled that Ranaldo agreed to take time out of his touring and recording schedule to curate an exclusive vintage guitar sale for Gilt MAN, which kicks off at noon ET today. We caught up with him during recording sessions for a new solo album (“it’s a song record,” the experimentalist says, “kind of a first for me”) to talk about his history with the instrument.

What was the first guitar you ever owned?

It was probably a tiny plastic guitar that had a picture of the Beatles stenciled on the body…a four-string ukulele, really. I also had a couple of inexpensive acoustic guitars when I was a kid. My first electric guitar I remember very vividly: It was a Swedish-made guitar called a Hagstrom II. I was 13, and it was a very big deal for me. It looked kind of beat-up, and I remember I spent a couple weeks stripping the paint off and then refinishing it in glossy black paint. That was the guitar I played in my first band, and I played it until I got a really serious guitar, which was an early-‘70s Fender Telecaster I bought off a friend of mine. It had that creamy white finish, like the one George Harrison played at the Concert for Bangladesh.

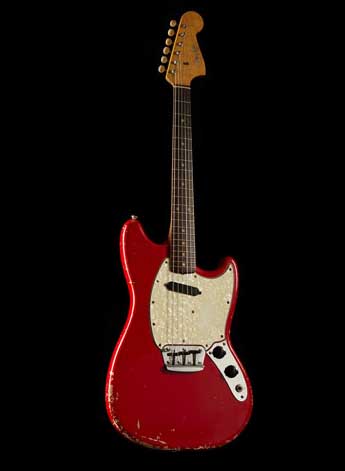

A 1964 FENDER MUSICMASTER RANALDO HAND-PICKED FOR THE VINTAGE GUITAR SALE.

And what was the first song you learned how to play?

Again, the Beatles. A friend of mine showed me how to play a couple of the acoustic songs on The White Album: “I Will,” “Rocky Raccoon,” stuff like that. And not too long after that an older cousin of mine taught me my first open tunings—he showed me how to play some Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young stuff that was in open-E and drop-D tuning. That really turned me on at the time. I got into them and Joni Mitchell, and from there into some older blues players like Reverend Gary Davis, people who were playing either slide or finger-pick styles with open tunings.

You’re a true innovator when it comes to guitar playing. Was there an experience or a record that really sparked that impulse to experiment?

The first Crosby, Stills and Nash record, and Neil Young’s After the Gold Rush were two records that really turned me on, ‘cause those guys were all playing around with open tunings and making their guitars sound really different in a really pleasing way. And shortly after that I discovered the work of Leo Kottke and John Fahey. Leo’s records were released on John’s label, and Fahey later became a friend, and I did a tour with him at one point. They were both very much playing almost completely in open tunings, and doing really radical stuff with what you could get out of a 6-string instrument. I mean, there’s no set tuning you have to abide by. Stringed instruments have been tuned to open tunings for hundreds of years…a whole new world of possibilities open up.

Speaking of innovation, you’ve become known for introducing all kinds of “foreign objects” to the guitar—drum sticks, screwdrivers…

Yeah. I had this band before Sonic Youth called The Fluks, and we did a couple songs that were sort of hinting at levels of extreme playing. I was playing an old guitar with a drum stick, and that later became something we did in Sonic Youth. One the one hand it’s got kind of a cool theatrical edge to it…You know, we were putting screwdrivers under the guitar strings. Mostly it was in the cause of sound rather than theater, but it definitely had an interesting element compared to everyone who wasn’t doing that kind of thing. With the screwdrivers, we started doing that because we were trying to figure out the ways strings actually make sounds, certain nodes along the length of a string; certain harmonics. A screwdriver creates a bridge, and you get more interesting sounds…and that’s what Glenn Branca was working on, moving bridges around underneath the strings, and seeing what kinds of effects you could get. We were doing it in a very seat-of-the-pants kind of way. And beating on the guitar with a drum stick—I mean, there are stringed instruments played with mallets, and this was kind of a more punk, brutal version of that. And once we got a little more savvy we were looking to experiments that guys like John Cage were doing, putting screws and other materials in the strings of pianos to get more percussive sounds, as opposed to open string sounds. And listening to stuff like Balinese gamelan music—metallic, attack-y, tuneful stuff. That music was always a big inspiration.

A 1967 SILVERTONE 145Z FEATURED IN THE SALE.

Guitars are aesthetic objects—whether you’re literally turning them into works of art, as you do, or whether it’s just that idea of guys being attracted to cool-looking gear. How much do looks matter to you?

These days, to me, it doesn’t matter as much how a guitar looks as how it sounds; but there’s always something about how a guitar looks. I think you can find something kind of cool about pretty much any guitar. And it’s partly about the variation on a stock form—most guitars take on a certain kind of shape and style, and yet there are so many different variations from one instrument maker to the next. Each guitar you pick up inspires you to do something different, based on what it is and what it can do. In the early days of Sonic Youth, we were really playing with the cheapest electric guitars possible, and we were discovering what they could do for us, how they could be useful to what we wanted.

When the band travels, we take 20, 25 guitars or more with us—on the one hand it’s kind of like being a traveling guitar store, and on the other it’s like each one you pick up has something very cool and interesting about it. The variation is part of the inspiration. I’ve got four sitting here in my living room, and each one inspires me to do something different. And they’re beautiful as artistic creations. When I was picking the guitars for the sale, I was really just looking for different ones that could represent a range of different things.

With all those guitars, how do you keep track of what’s what, when you’re on the road?

Well, we’ve got crew guys who help with that. There’s a big guitar rack on each side of the stage—mine on one side, and Thurston [Moore]’s on the other. I mean, the easiest way to organize them, because I use a lot of guitars that are the same model, is by color. And tape marks on the side of the guitars to tell us what’s what…I’ve got a whole bunch of a certain kind of Fender Telecaster, and they’re numbered, like, 1, 2, 3, and 4…That tells us what tuning they’re in. And you get to know that, when you’re about to play a certain song you need the blue guitar, or the white guitar…

What are the main things you modify on your guitars, from a technical point of view?

The pickups are probably the most important modification. At this point there are certain pickups I just really like the sound of, which I put in a lot of my guitars. And we modify the electronics to make them more road-worthy. A lot of the guitars we like are older, vintage guitars, like some of the ones that are in the sale, but if you’re taking them around the world and beating on them, sometimes the electronics aren’t really up to the task. So we strip away a lot of the stuff that’s not necessary, and keep just the most elemental stuff: a volume knob; the wires between the jack and the volume knob and the pickup. We take out tone controls and odd switches that don’t really do things we need. And often we modify the bridge, where the strings run over, at the base of the guitar—we have preferences of what we like there, for the physical way we play.

Back in 1999 you had an experience that’s pretty much every band’s nightmare. A massive amount of equipment was lifted from your van.

The whole van was lifted! [laughs] We were at a hotel in Southern California, and the entire van was stolen the night before we had to play a big festival show in Orange County, in front of 25,000 people…

A 1968 GRETSCH RALLY FEATURED IN THE SALE.

For a band that’s so passionate about its gear, what was the experience of waking up to that like?

We felt really violated. It was kind of hard to believe. We had built the stuff up over 10 or 12 years to be exactly what we needed to get our sound. We had slowly evolved this set of gear, through trial and error, that was helping us produce our sound. And then it was all stripped out from under us. Luckily we had a lot of friends who were in bands on the bill of that concert, and we ended up just borrowing bits and pieces of all kinds of gear that day to play our show. Guided By Voices, and one of Mike Watt’s groups, and pretty much everyone else was handing our crew guys their guitars, and our guys were snipping strings off and putting our string gauges on, and fixing them up as best as they could. We’re pretty well past it at this point, and one of the things the experience solidified for us, oddly, was that it let us know that what we do with our music is ultimately not about the gear, but it’s about the sensibility of the players. We scrambled around and found a lot of weird gear that we used for the rest of that tour and on the next record, as we were slowly building back an arsenal of our own, and it still came out as Sonic Youth music. We realized we’d evolved a certain kind of language together that transcended the gear.

You’ve since recovered some of that equipment, right?

We recovered four guitars, out of an entire truckload of stuff. We actually met some young kids in Southern California who knew about the theft, and were providing us with information, and helped us get back some of the guitars. But we were talking about this yesterday…Literally a huge amount of gear was lost—amps, drums, tons of guitars, pedals, the whole thing. And only four have actually turned up on the open market.

The 1991 film The Year Punk Broke will soon be re-released on DVD. It’s a movie I watched countless times with my friends in high school. Was there a sense that playing in front of those massive crowds marked a real shift for you as a band?

A bit, but a lot of it was the circumstances of that tour, and the fact that we were playing with Nirvana, right before they busted through and got huge. But it was also, a lot of the other groups on that particular tour—Dinosaur Jr., Babes in Toyland… It just seemed like it was our time, that we were being recognized, not just as Sonic Youth, but as a whole grouping of bands that had become friends over the years were being recognized by a wider public. The DVD’s gonna have lots of great extra features and things, so we’re super psyched about it…

What’s next for you, and the band?

Well, I’m working on this solo record. And we’re involved in so many things these days musically. We’re talking about doing a bunch of dates over the course of this year, including a summer Sonic Youth show in Williamsburg at the band shell in mid-August. We’re gonna get together and have writing sessions for our next record. I’m going out on a solo tour in early May in Europe to do experimental guitar stuff—it involves films, and I suspend my guitar from a line in the ceiling and play it with a bow and swing it around, and work on other kinds of sounds you can get out of a guitar…not song-like at all, but much more abstract and environmental, in a way.

Gilt MAN Finds: Vintage Electric Guitars curated by Lee Ranaldo of Sonic Youth.